Prepared by Mr. Eugene Yapp, Adjunct Lecturer

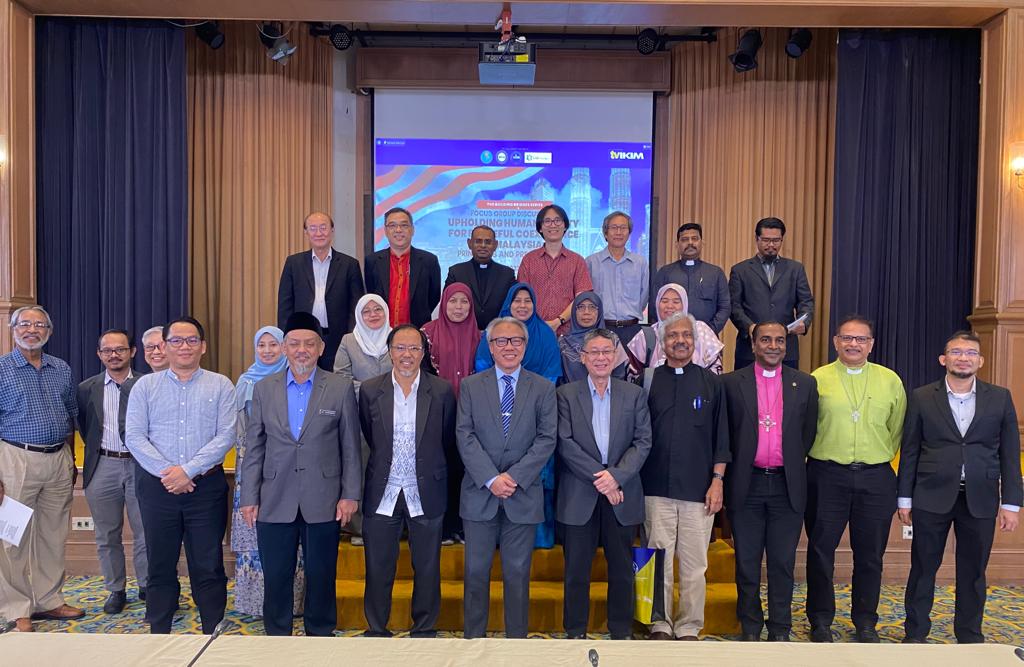

There is much to commend a conversation especially when we can find common grounds for a common cause. Such is the case when we consider the theme of human dignity. In a special focus groups discussion session jointly organised by the Institute of Islamic Understanding (IKIM), the Seminari Theoloji Malaysia (STM), BYU Center for Law and Society and the local NGO, UID-Sejahtera Malaysia held on 18 January 2023, a number of Christian and Muslim thinkers came together to examine and unpack this theme more closely.

Human dignity is not an idea. Nor is it idealism or ideology leading to materialism and pragmatism. It is rooted in religious traditions that speak to life and what life ought to be. It expresses itself in the universal moral values common to mankind for the wellbeing of all people.

At the focus group discussion, we heard that within the Islamic tradition there is the concept of “mahabbah” meaning to love to God and love for the other, love to one’s neighbour. This is not a strange concept to Malaysians. The root Arabic word is where we derived the Bahasa Melayu word “Muhibbah” which we all well know its meaning. By extension but with some variation, the Christian revelation that man was made in the image of God – the visible expression, the mirroring of the character, attributes and capacity of God in man is to find its ultimate fulfilment in the command to love our God with all our hearts, mind and soul and to love our neighbour as ourselves.

The common quote by Immanuel Kant comes to mind here, ‘so act that you use humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means”. (Kant, Metaphysics of Morals). While Kant’s moral philosophy is rooted in idealism and finds its ground in the autonomous rationality of man, the inescapable observation that man should never be the means to an end but the end itself is noteworthy. Man stands in a unique stature because we are created in the image of God. The Biblical tradition explicitly express the glory of man is such majestic terms “what is man that you are mindful of him” and provides the contrast with God’s other creation. Endowed with the will to exercise the mandate God have to man and the capacity for relationality, man stands in unique relationship with God and his creation. He is in other words the crowning glory of God’s creation and having the majesty not possess by other creatures.

It is this that human dignity recognises – that all human beings are valuable and have possess an intrinsic value in themselves and so deserves the honour and respect due to him not because of his or her own stature but by the very fact we have been created by God having a unique and special stature according to the very purposes of God himself. Human beings are created for good just as God has declared of all His creation as “good”. Human beings are capable of doing and bringing that good to the creation order that is laden with the potentialities for the good that God intended. It therefore demands that we as human beings treat and demonstrates sociality and the bonds of social relation in practical visible expression of love, kindness, goodness to those around us as marks of respect and honour to our fellow human beings. Dignity in this sense is what some has called it “diapraxis” or what I would term as based on the “lived experience” of people.

There are off course gaps with those who may not see much in the concept of dignity owing to its abstract conception or simply because it’s of no concrete use. I suspect when it comes to gap, the difficulties lie more with those who are of the more extreme or militant secularists rather than with those who are religiously orientated. There are those who would frame the debate or prefer to categorise the problem as between the “conservatives vs progressives”. Religious groups will be categorised as conservatives and outmoded. The impression given is religious people do not subscribe to pluralist democracy and will be seen as wanting to impose our “comprehensive doctrine” on others. Such dichotomous thinking is already present here through the efforts of those who have a more secularists frame of thought where anything to do with the religious is bad and should therefore be confined to the private.

But dignity is not a comprehensive doctrine. There is a place for conceptions and the abstract. But it is life and lived experience which cannot be denied. Within the Biblical narratives, that life or lived experience is lodged within covenant obligations of a covenant community; first in the nation of Israel then in the universal church as the people of God. As the covenant people of God, we have the moral and ethical injunction to love mercy, do justice and walk humbly before the Lord (Mic 6:8). This injunction corresponds very closely to the imperative given by our Lord himself to love the Lord and to love our neighbour with all our hearts, mind and soul.

This moral and ethical injunction therefore carries with it a social obligation premised upon the social identity of Christians as the covenant people of God. This social obligation is not merely within the church but obliges us to forge common consensus in a pluralist society for a multicultural form of social life where all can and have the place to seek the welfare of the city and a social order that enables human flourishing and human wellbeing. Human dignity unpacks this way see the respect due to the other not just on individualistic terms but very much oriented to community and the whole of societal life. In short its about the bringing of good to all people of the earth, in the material and spiritual benefits for all mankind.

The church must therefore walk worthy of the Lord’s calling. She cannot be content at the side lines nor neglect her social obligations. Otherwise, she loses her place in society by default and seen as irrelevant. It demands that Christians uphold human dignity not as some abstract conception fit only for academic life but in practical expression for all people especially to those who are victimised and marginalised.

How this pan out within the notion of a civil society increasingly becoming more variegated and diverse, within the broader conception of democratic life and equal citizenship, the rights of the minorities along with the duties of the majority, the economics of the free-market movement and with those whom we often to do not associate with such as the LGBTQ community, the feminists and gender equality movement are the challenges and contestation we will soon face. It is naïve to think we can resolve all such issues and challenges. But Christian mission demands we posit a framework of action – where possibly the whole idea of dignity becomes an overarching tool to move debates beyond overlapping consensus towards harmonious life, mutual understanding and the coming together to seek the common good and a public justice for all people.

There is much to be done, but we are making small steps along the way. The symposium in July will be key as more diverse group of people representing differing viewpoints will be invited to give their views.